By David Morton, Jr.

Reviewed by Matt Frazier.

Early attempts at sound recording were a bit like my own pre-teen efforts at coding a card game in BASIC—interesting and mildly promising, but resulting in a marginally useful outcome. Recording on tinfoil? Wax? Even compared to an 8-track tape, that is downright primitive. The long and winding road from the “phonautograph” recording demonstration in 1857 France to the ubiquitous MP3 of today is full of wrong turns and stubborn resistance to change (new Edison wax cylinders were still available for purchase into the 1960s, for example). Sound Recording: The Life Story of a Technology is a helpful guide to the journey.

David L. Morton Jr. doesn’t go light on early developments. That his middle chapter is “The Crucial 1930s” illustrates as much. Incidentally, that decade proves a poignant example for comparison to our own time. The combination of the expansion of broadcast radio and the Great Depression dealt a severe blow to the record industry. In this time of uncertainty, however, recording technology developed significantly. Alan Blumlein demonstrated the first “binaural” recordings, acetate discs dramatically improved the economy of recording, and the wide deployment of jukeboxes created a future market for records (which wore out easily) and provided a new kind of access to and for music consumers. With the music industry currently in a time of drastic transition, it is worth pondering the possible positive impact of innovations in development now.

Sound Recording is well-crafted, if a bit staid. But intrigue is just below the surface. Alexander Graham Bell designed and tested a recording device using an actual human ear and part of a skull from a cadaver. Edison tried to develop a talking doll with a small cylinder player inside (spoiler alert: that didn’t work out). And in the 1950s, the New Jersey mob ran a record pirating ring from its own large duplicating plant. In all these accounts, one thing becomes extremely clear—the history of recorded sound is full of change with various winners and losers along the way. Sound familiar?

By Greg Milner

Reviewed by Matt Frazier

Like all good history, Perfecting Sound Forever provides perspective. What is the most significant divide in the story of recording technology? Analog vs. Digital? 33 1/3 vs. 45? Acoustic vs. Electric? Cylinder vs. Disc? Exactly. Turns out, we’re not the only generation with competing ideas about what sounds (and works) best. (Even microphones were once controversial!) Greg Milner presents a nuanced and balanced discussion of each competing (and enhancing) development over the years.

Milner also highlights important connections between commerce, broader social forces, and technical innovations in recording. For example, compelling cases are made for how radio impacted listeners’ expectations for recorded sound, (dating from the 1920s until the Loudness Wars of the late 20th century). The perplexing mystery of the movement toward diminished dynamic range in recorded music (just as CDs delivered so much more of it) is thoroughly explored. We even learn of a surprising link between the oil industry and Auto-Tune.

From Thomas Edison’s Mary Had a Little Lamb in 1877 to the development of Pro Tools and mixing “in the box,” Greg Milner pretty much covers it all. And he covers it well, getting the majority of the technical details and explanations right along the way. Most importantly, Milner seems to grasp the profundity of recorded sound—the dead can even speak to the living through this nearly magic technology we so often now take for granted.

By John Szwed

Reviewed by Matt Frazier

Muddy Waters, Leadbelly, Jelly Roll Morton, and Woody Guthrie—not too shabby as discographies go and Alan Lomax recorded them all (and countless others). Record producer, song collector, musical anthropologist, and writer, Lomax was deeply driven and remarkably productive. He even devised entirely new methods for studying and classifying songs that, arguably, laid the conceptual groundwork for Pandora’s Music Genome Project. Though he generated a copious amount of groundbreaking material, Lomax lived perpetually broke and sometimes flat-out broken.

Author John Szwed knew Lomax personally and this always-respectful account is researched with the rigor of academia. Though Szwed’s narrative becomes bogged down in chronological detail occasionally, he can be forgiven his commitment to such an accurate account that moves from town to town, state to state, and country to country so rapidly and frequently. In the end, Szwed reveals Lomax as passionate to enable culture to grow again “on the periphery—where culture has always grown.”

The democratization of musical recording is often thought to have begun 10 or 15 years ago when suddenly almost anyone could record music. The field recording work of Lomax and his contemporaries, however, was the first such wave in the brief history of capturing sound. (Lomax schlepped his portable studios—ranging from an Edison-designed cylinder recorder to an Ampex 601-2—into prisons, churches, and across sharecroppers’ fields.) Yes, almost anyone can record nowadays. But with Lomax, almost anyone could be recorded. Alan Lomax would certainly note this important distinction.

Reviewed by Matt Frazier (originally published in Tape Op)

Like all good history, Perfecting Sound Forever provides perspective. What is the most significant divide in the story of recording technology? Analog vs. Digital? 33 1/3 vs. 45? Acoustic vs. Electric? Cylinder vs. Disc? Exactly. Turns out, we’re not the only generation with competing ideas about what sounds (and works) best. (Even microphones were once controversial!) Greg Milner presents a nuanced and balanced discussion of each competing (and enhancing) development over the years.

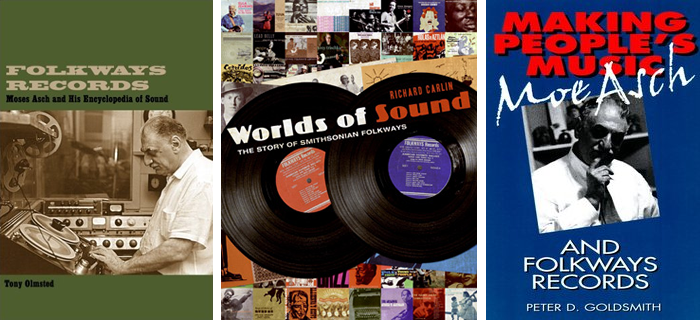

Tony Olmsted’s Folkways Records: Moses Asch and His Encyclopedia of Sound approaches an understanding of Asch’s work via a thorough examination of business documents from the Folkways archives. It is, perhaps inevitably, sometimes as mundane as invoices and inventory reports can be. For anyone interested in the particulars of operating an independent record label in the 20th century, however, it’s an insightful account.

In Worlds of Sound: The Story of Smithsonian Folkways, Richard Carlin breaks down the distinct eras and styles of material captured by Folkways (including its current incarnation as part of the Smithsonian). Though little is revealed about Asch on a personal level, the book is enlightening and exhaustive in scope otherwise. Given Asch’s pioneering approach to record packaging, Carlin’s illustrated offering is gratifying.

Unlike the other two works considered here, Making People’s Music: Moe Ash and Folkways Records by Peter D. Goldsmith is an actual biography. Sometimes excessive cultural, sociological, and political context is provided but the reader is certainly guided carefully through Asch’s world. Given the depth of Goldsmith’s research, this is not a book to take on casually. Ultimately, Goldsmith reveals Asch warts and all—a man of principle (politically, if not personally) who prioritizes artistic integrity over commercial possibility.

Moe Asch was a true iconoclast. An independent label executive who avoided music venues and recorded only with the utmost transparency (one microphone, no splicing or overdubs, no EQ). In spite of his sometimes-difficult demeanor (not to mention the promise of only modest financial reward), artists came to him repeatedly because Asch accepted and validated their vision in a way no other label would. The result is a collection of over 2000 records now housed and (still) distributed by the country’s foremost museum of culture and history. As Asch and Einstein originally discussed, it’s the sound of the world and a world of sound.

By Kent Hartman

Reviewed by Matt Frazier

Once upon a time, before phablets, before Myspace, before even cable TV, music was HUGE. So huge that the Beach Boys (featuring Glen Campbell on bass) toured the country while Brian Wilson hunkered down in LA recording new material for his band. So huge that new record labels were popping up all over Los Angeles. So huge, in fact, that Phil Spector could hire three bass players for a single session. Yes, I’m pining.

Which isn’t to say The Wrecking Crew is a complete joy to read. Overall, it bears the hallmarks of a manuscript in need of stronger editorial oversight. There are too many players covered for much depth to emerge. The reader will have to excuse overly dramatized anecdotes, unnecessary details that clutter the arc, and forced cliffhangers. While much of the content is engaging, frequent hard stops in the narrative are no substitute for carefully interwoven storylines.

Literary shortcomings aside, Hartman does us (and his subjects) a service simply by digging up the details from “music’s version of the California Gold Rush.” Covering Hal Blaine, Carol Kaye, Jimmy Webb, Herb Albert, and so many others, Hartman reminds us that pop music is a business. Even when executed artfully, the goal was (and is) mass consumption. In other words, a hit—the bigger, the better.

By Jimmy Webb

Reviewed by Matt Frazier

Jimmy Webb scored giant hits. Often without even writing proper choruses! (Granted, that was a different time and members of the general public still employed moderate attention spans. But still.) Sympathetic to a Brill Building (if not Tin Pan Alley) sensibility, Webb may be easy to dismiss as past his prime. But it would be a mistake to discard the hard-won insights and instruction offered en masse. Tunesmith is a broad and interesting look at how a master approaches his creative discipline and business.

The writing here is vulnerable, opinionated, gracious, and wry. Like Webb’s songs, the material is sophisticated, witty, and perceptive. He covers conceptual issues like professional versatility as well as specific techniques of harmony, lyrical meter, and other nitty gritties of the craft. Some of the music theory is perhaps a bit much (every major scale spelled out on a staff, the complete circle of fifths diagrammed, etc…) but the presentation is thorough. There is also regional guidance (for New York, Nashville, and Los Angeles) that can best be appreciated as recent history (the book was published in 1998 and much has changed since).

Perhaps the best element of the book is Webb’s demonstrative tour of writing a complete song. Every stage is covered: first-draft mechanics (with real transparency); self-critique (and doubt); revision (and more revision). There are extensive chapters on lyric, melody, and harmonic writing as well as song analyses a plenty. Webb never takes himself too seriously, but this is certainly a serious book about a culturally significant endeavor. Even after 422 pages, however, you still will not know why a cake was left out in the rain in MacArthur Park. I’m just sayin’…

By Stephen Witt

Reviewed by Matt Frazier

Given the subject (i.e., the digitization of the music business), you might not expect a page-turner from How Music Got Free, but journalist Stephen Witt has created one. His inquisitive impulses (and snark to spare) take readers on a tour from Germany to Los Angeles and many points in between. We meet dedicated scientists, disaffected basement dwellers, and record label honchos with outsized salaries. The main character, however, is a (mostly) sympathetic bootlegging hustler and factory worker in the sticks of North Carolina.

Dell Glover just sort of fell into pirating. He quickly displayed a knack for it, however, and eventually became world class. Though it did create an indirect income stream for him, we never fully understand why Glover goes to such lengths. In essence, pirating consumes his life and the one time he tries to go cold turkey, it doesn’t take. All told, he leaked over 2000 records before their release dates.

How Music Got Free is an expansive consideration of the decade (or so) that turned the music business upside down. Storylines rotate by chapter, which may become tedious for some readers, but the device is generally successful at creating the sense that apparently unrelated events in disparate parts of the world connect (often intricately so). It’s a quick read and a fun ride: Oversized belt buckles almost kill the music industry; professional hockey saves the MP3 (from the MP2); and Oink’s Pink Palace builds a larger collection of music than iTunes. Stephen Witt helps us understand the tectonic cultural shift that made music free.

By John Seabrook

Reviewed by Matt Frazier

If you’ve taken the last couple decades off from Pop music in America (and honestly, who could blame you?), John Seabrook’s The Song Machine is a helpful primer to understanding what the Swedes have wrought. Channeling an African American-ized, ABBA-esque sensibility through the voices of Brittany Spears, the Backstreet Boys, ’N Sync, Kelly Clarkson, and Taylor Swift, Max Martin and a host of other top-lining, beat-making, far northern European writer-producers have certainly left their mark.

Seabrook posits that the Swedes (apparently, a singsong-y lot of bored farmers) were uniquely positioned to reinvent Pop music in America. Even their second language command of English is an asset when writing for da club (“Lyrics that command too much attention are likely to kill the dancing.”). Seabrook also covers the rags to Pitches story of Ester Dean; the synth treacle of Stargate; and the many and varied peculiarities of Dr. Luke. All the while hearkening back to previous song factories like the Brill Building and Motown.

Seabrook’s forays into specific concepts of music and production sometimes go awry. “Digital compression” was Butch Vig’s critical contribution to Nevermind? The TR-808 was the first programmable drum machine? Such dubious perspectives distract from what is likely an otherwise credible account. If you can overlook these missteps, Seabrook’s work is a valuable, even palpable, reminder that Pop music is about attitude and vibe—the personality of the performer, the track, the beat.